2024.05.28 – 06.22

Opening hour: 12.00-18.00

Closed on Sun, Mon, National holiday

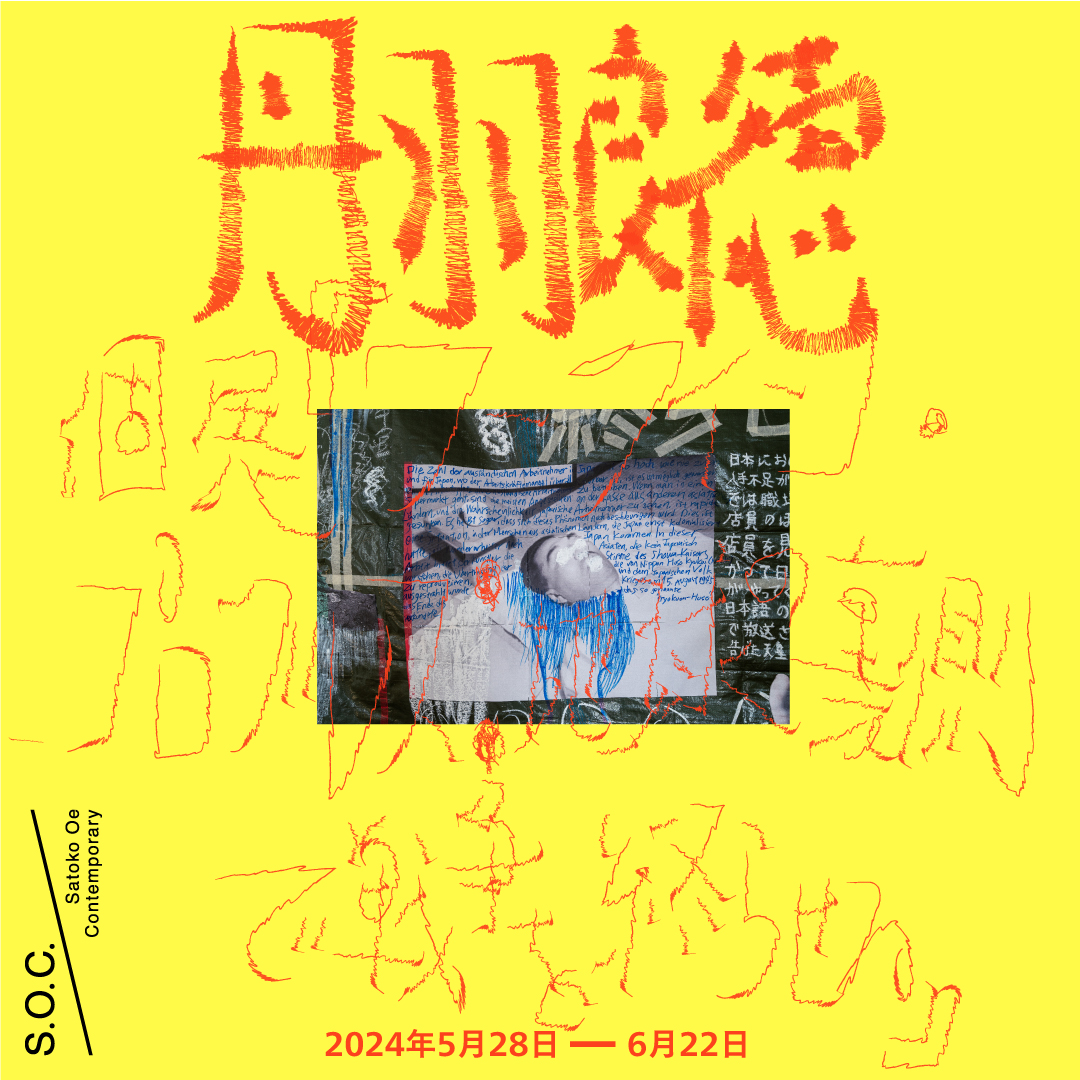

The collage drawings created as instructions for the social practice “Ending the War on the Other Side of the World” (2023-), which is currently in production, are drawn on waterproof blue sheets.

The text explaining the content of the work, and the face of Emperor Hirohito and the former Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, who committed suicide by poisoning potassium cyanide, are largely drawn. Nearly 80 years have passed since the end of the world war II, and the number of generations that experienced war has decreased, and the form of society has changed significantly.

It has changed to welcome workers and students from Asian regions once invaded by the Japanese military. This artwork attempts to think about what war is like in the context of global change by recreating Emperor Hirohito’s Gyokuon broadcast by this visitor from Asia.

Yoshinori Niwa plans to complete this work within the next few years. This exhibition will feature new and recent drawings created in Vienna, centering around this collage drawing, as well as a video work titled “Selling the naming rights to a garbage mountain” in 2014 set in a garbage landfill in Manila, Philippines.

We are pleased to announce the group show of “ONSEN CONFIDENTIAL The Final!!” starting from 6th through 20th April.

2023.07.22 – 09.02

Opening hour: 12.00-18.00

Closed on Sun, Mon, National holiday, between 08.12 – 21

Scarecrow

Almost half a century ago, maybe when I was in junior high school (my memory is hazy), I watched a movie starring Al Pacino and Gene Hackman. It was a dismal tale of a couple of scruffy vagabonds drifting around rural America, and the title, Scarecrow, somehow stuck in my mind. The English word meant nothing to me at the time, and perhaps I was simply drawn to the sound. The film portrayed the misery and rage of outcasts, men who society scorned as hoodlums or drunken bums, and it conveyed the atmosphere of present-day America, which seemed extremely remote and exciting to a Japanese kid from the sticks. At that time many movies coming out of the West revolved around outlaw stories like this, and I think they may have had a profound impact on my adolescent mentality.

It was not until much later that I learned the meaning of “scarecrow,” which is kakashi in Japanese. After that, when I was in art school, I saw The Wizard of Oz, and the brainless scarecrow character made a lasting impression on me. I’m not sure why this was, but it may have resonated with some void or absence I perceived within myself. I may have unconsciously projected myself onto that straw man. I think it was around that time that I finally made the connection between kakashi and “scarecrow.”

Be that as it may, when used in a metaphorical sense the implications of the word are rarely positive. We picture a lonely outcast standing around idly, someone useless and incompetent despite having a designated duty to fulfill.

In Japan at least, actual scarecrows in fields are often mishmashes of junk and old worn-out clothing, made without craft or attention to detail and barely registering as humanoid figures. At the same time, a vaguely humanoid form is really their only defining feature. For the past ten years or so, I’ve been strangely fascinated by these hollow and senseless entities.

Two years ago, I had a solo show and took the title of one of the works from Millet’s painting The Sower. It was just a title without any deep meaning, and it didn’t signify the things that motivated Millet, like devout faith or empathy with farmers. I depicted a purposeless humanoid figure made by piling up or binding together vegetables, fish, sticks and stones. A being without a brain, a heart, or a narrative. In a way it was like a scarecrow. The cobbled-together figure in the painting had outstretched hands, in a pose reminiscent of a sower.

The sower and the scarecrow… it fit together nicely.

What we in Japan describe as art or painting, including the modern and contemporary variety, to this day is mostly nothing more than a patchwork of imitations of the West, a hollow and superficial sham. It’s a constant effort to conform to overseas values, to create works that feel safe and familiar to both the artist and the viewer, who are in a relationship of cozy complicity.

These things look the part, but they lack substance. For as long as anyone can remember, they’ve been like stuffed scarecrows with no real substance. Maybe this is why I feel drawn to scarecrows.

At the edge of the field where the seeds of Western art were sown, there stands an empty and worthless scarecrow, patched together from cast-off scraps… this is the scene I picture in my mind’s eye.

Shigeru HASEGAWA

2023.04.15 – 05.20

Opening hour: 12.00-18.00

Closed on Sun, Mon, National holiday

*We will be closed between 04.29 – 05.08.

In this exhibition, Why does humankind engage in economic activity?, the artist Yoshinori Niwa presents videos, drawings, and neon works. These works shed light on how the human identity is shaped by capitalist society, which is premised on mass production, mass consumption, and mass disposal, and its products.

As Niwa was active in performance art for many years, the titles of his works hold special significance for him. In the past, nearly all of the titles ended in “-ing.” Niwa’s videos, which document his performances, are just one more example. In essence, they are presented as a public protocol that can be used by anyone.

In the wake of the novel coronavirus pandemic, Niwa expanded his performance works by embarking on a new series of collages in which he combined supermarket fliers that were deposited in his mailbox everyday with pictures from newspapers and masking tape. Alongside images of meat, sausages, clothing, and mass-produced industrial goods, a variety of actions (i.e., titles) are specified in large Japanese and German writing, as a critique of capitalist society, against a backdrop of innocently smiling models. Niwa made the majority of these works at his studio in Vienna.

In recent years, Niwa staged the Narrating our possessions, 2022 performance, in which he randomly read legible words over the telephone in a public space in London as he crawled through the street toward the gallery. He was also invited by the Prameya Art Foundation to place an ad in a Dehli newspaper, and in a citizen-participation project called Living in someone’s possessions, 2023, he temporarily borrowed various things from ordinary people and attempted to imitate their daily lives. All of these works raise questions about the human race, which finds itself at the mercy of capitalist society with its concomitant mass production, mass consumption, and mass disposal. Although we all share a hatred for capitalism, it is impossible to refrain from taking part in economic activities. It is within this sad state of affairs that our identities seep out.

Supported by the Austrian Cultural Forum Tokyo

2022.10.15 – 11.06

Opening hour: 12.00-18.00

Closed on Sun, Mon, National holiday

We are pleased to announce an exhibition by two painters, Yuka Shiobara (b.1985) and Yuuka Ishii (b.1995) at our gallery.

At first glance, there are motifs and painting styles that seem to have been drawn in past masterpieces and hobby paintings, but the method of selection and judgment, and the way they are drawn are greatly different, and the individuality stands out. In the information society, those masterpieces are actually seen by them, and also they have only seen them in the image. In particular, each artist is careful when extracting decorative elements that are repeatedly used in paintings and restructuring them into their own works. Please take this opportunity to see the two-person exhibition, Shiobara who makes her individuality invisible by repeatedly using the characteristics of a masterpiece in her own work, and Ishii, who makes her individuality visible by working against it.

We look forward to seeing you.

2022.9.10 – 9.24

Opening hour: 12.00-18.00

Closed on Sun, Mon, National holiday

Sponsored by Ken Kagami, Cafe Sunday, uruotte, Utrecht

Special thanks : Hikotaro Kanehira

Travel agent : JTB

Media sponsor: Contemporary Art Library

Initiated by Jeffrey and Misako Rosen, COBRA

We are participating “Onsen confidential 2022”

What is Onsen Confidential?

Onsen Confidential is a hybrid city-wide gallery share and natural hot spring retreat/conference. The project is meant to bring together like-minded gallerists in a spirit of collaboration and cooperation and to provide a friendly introduction to the unique context of the contemporary art world of Tokyo.

Initiated by Misako & Jeffrey Rosen of Misako & Rosen, Tokyo and COBRA of XYZ Collective, Tokyo

We are pleased to host Good Weather from Chicago, USA, and A THOUSAND PLATEAUS ART SPACE from Chengdu, China. The participating artists of our show are Dylan Spaysky, Inga Danysz, Chen Qiulin, and Tadasuke Iwanaga.

We look forward to seeing you.