2024.05.28 – 06.22

Opening hour: 12.00-18.00

Closed on Sun, Mon, National holiday

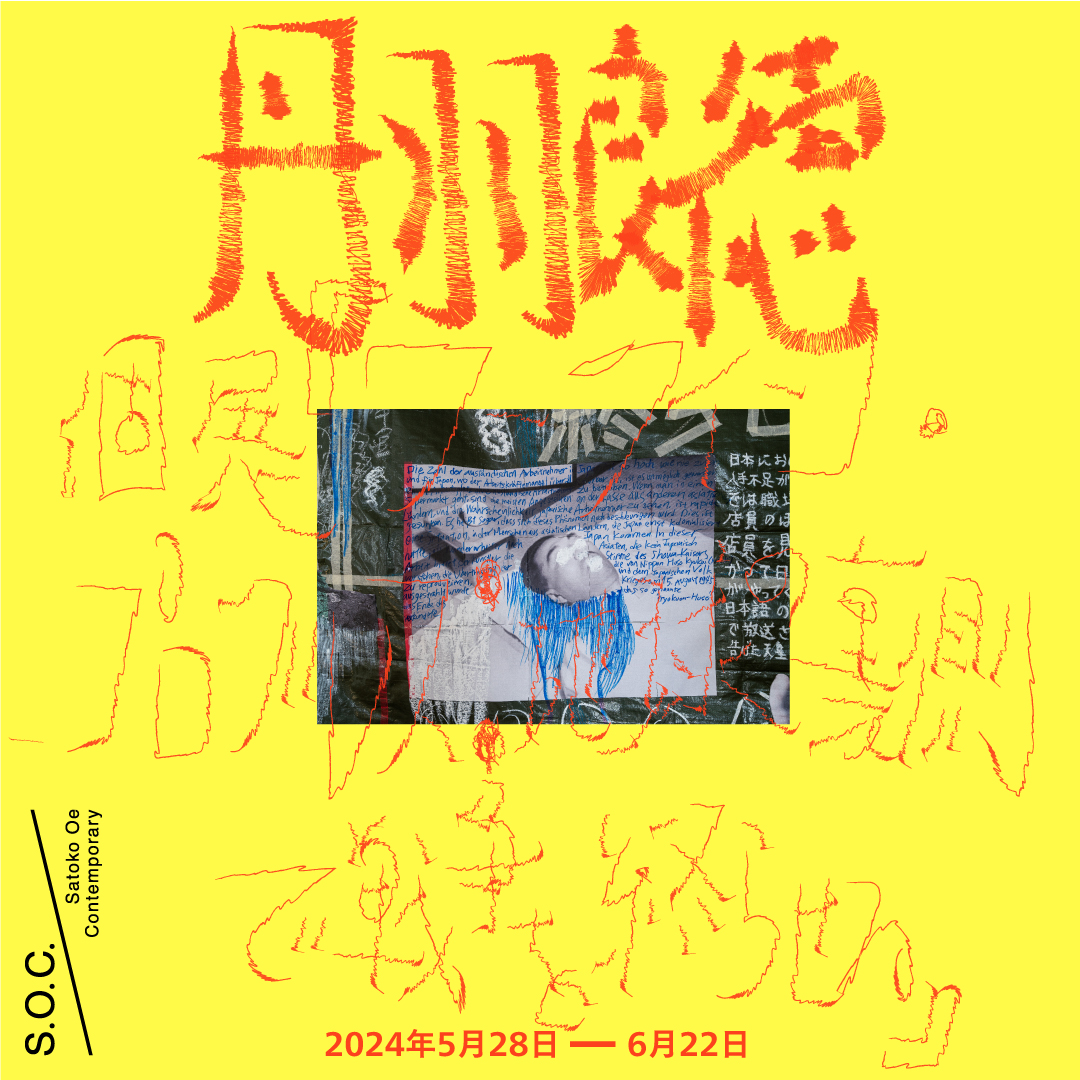

The collage drawings created as instructions for the social practice “Ending the War on the Other Side of the World” (2023-), which is currently in production, are drawn on waterproof blue sheets.

The text explaining the content of the work, and the face of Emperor Hirohito and the former Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, who committed suicide by poisoning potassium cyanide, are largely drawn. Nearly 80 years have passed since the end of the world war II, and the number of generations that experienced war has decreased, and the form of society has changed significantly.

It has changed to welcome workers and students from Asian regions once invaded by the Japanese military. This artwork attempts to think about what war is like in the context of global change by recreating Emperor Hirohito’s Gyokuon broadcast by this visitor from Asia.

Yoshinori Niwa plans to complete this work within the next few years. This exhibition will feature new and recent drawings created in Vienna, centering around this collage drawing, as well as a video work titled “Selling the naming rights to a garbage mountain” in 2014 set in a garbage landfill in Manila, Philippines.